Sorry for the delay in an end of season summary but it was quite a whirl wind once we summited Denali, returned to Talkeetna, and traveled back to our respective home states. The main take home points from the season include:

- Blaine and Kristin were able to install a USGS survey marker at Windy Corner (13,500 fasl) for long term monitoring of tectonic movements in the Alaska Range. Just as importantly, Blaine was able to record GPS information over the marker with our GPS base station for over 5 days which will be a great first year dataset for comparison to measurements in the following years.

Blaine with the newly established USGS survey Marker at Windy Corner.

- Patrick was able to collect snow samples at Kahiltna Basecamp (7,600 fsal), Kahiltna Pass (10,200 fasl), Camp 14 (14,200 fasl), and High Camp (17,300 fasl) for comparison to the snow chemistry at the ice core drill site our collaborative team drilled at Mount Hunter (13,000 fasl) in 2013. This information will help us understand atmospheric chemistry as a function of elevation in the Alaska Range which is important for interpreting our ice core record we recently acquired.

Patrick digging a snow pit to collect snow samples from for comparison to the Mount Hunter ice core collected in 2013.

- We were able to collect ground-penetrating radar ice thickness measurements from the summit of Denali! This was the final challenging science endeavor of the season and included carrying the radar and GPS equipment to the summit as a team. Kudos especially to our young and very strong Patrick who carried both a car battery and the GPR control unit while the GPS gear, cables and radar antenna was split between Kristin and I.

Kristin and I collecting GPR data at the summit of Denali

Did I say car battery? Well… that’s not entirely correct. It was ONLY an 18-amp hour 14-pound battery that Patrick carried, along with the 10 pound GPR control unit. (I say ONLY, jokingly). Normally 60 extra pounds of gear spread between three people would not be a big deal, but the reality is, carrying that extra weight of science gear to the summit of the highest point in North America, along with the technical climbing and safety gear we needed to carry, is no small feat for a mere mortal research team. We were happy to try it, but the extra effort beyond what climbing teams were expending to reach the summit, was certainly enough of a workout for all of us. BUT, I digress and am jumping ahead of myself here. Let me tell the entire story from Camp 14 to the summit and back…

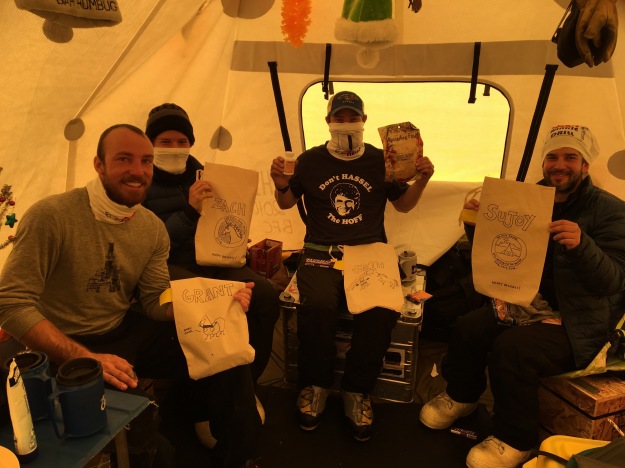

Friends at basecamp! (L to R) Dom Winski, Jimmy Voorhis (guiding on the mountain but prior MS student at Dartmouth), Patrick, myself, and Kristin

About 1/2 way to Camp 1 (which is at 7800 fasl). Only 12500 feet in elevation gain to go for the summit of Denali (background)!

Patrick cooking up a hearty dinner in our camp 11 snow cave!

Lounging in the Camp 11 snow cave while I wait for snow to melt for water!

Looking up Squirrel Hill from the top of Motorcycle Hill on one of our acclimatization and cache days to Camp 14.

Kristin moving up Squirrel Hill with Peters Dome (back right) and Peters Glacier (below right).

Me at the top of Motorcycle Hill (12000 fasl) towing the radar gear and solar power panel with a duffel full of food under the panel. We left the panel at Windy Corner with the GPS base station, thankfully!

On the same day that Blaine and Kristin installed the USGS survey marker at Windy Corner, Patrick and I shuttled a huge amount of science gear, food, and supplies to 14,200 fasl from the 11,000 fasl camp. Kristin and Blaine joined us at Camp 14 with some extra supplies after they finished the survey marker installation. We returned to Camp 11 for the evening, and on the following day, moved the rest of our gear, camp, and ourselves to Camp 14.

The duffel of food and a couple containers of fuel!

The team at a possible cache site above windy corner and below Camp 14. We cached our gear at Camp 14 to cut a day out of our travel efforts so we could relax and rest a little more!

Once our entire team arrived at Camp 14, we settled in and started shuttling gear to higher cache sites the following day; first from Camp 14 to 16,400 fasl and a second beautiful day hike from Camp 14 to high camp at 17,300 fasl. These two shuttle days helped us stage all our gear for a summit attempt and to acclimatize properly at higher elevations. We then had some relaxing rest days at Camp 14 because of poor weather and also because we needed to trouble-shoot a few technical difficulties. The cold temperatures were a little rough on some of the GPS cables, but after troubleshooting the cable issues (with assistance from the great park climbing rangers) we were able to get our GPS and GPR equipment all working properly. We then installed the GPS base station over the USGS survey marker at Windy Corner with a 20-pound solar power panel, that we also hand carried up to the corner from base camp. We hoped to record at least 48 hours of GPS data over the new survey marker as a first year of data for comparison to future years.

Evening view from Camp 14! Mount Foraker (right) Hunter (left) and the moon…. BEAUTIFUL!

During our stormy weather at Camp 14 (which was relatively mild), Camp 17 received sustained 80 mph winds over the course of one day and up to 50-60 mph winds during the other storm days. We were happy that we decided to wait out the storm at lower elevation once we heard that news! After three days of rest at Camp 14 due to the weather and equipment issues, we had a great weather opening to climb towards high camp.

Climbing past Washburn’s Thumb about 16800 fasl on the West Buttress of Denali. Coolest part of the climb we all agree!

Patrick (left) and Kristin (right) on the awesome ridge between Camp 14 and Camp 17!

Another amazing ridge view!

And another!

One of the comical decisions of the trip was regarding our tent decision for high camp. During the climb to Camp 14, we had used two The North Face VE-25 tents for sleeping quarters and a Hilleberg as a cook tent: plenty of room for four people. BUT, to save weight and account for the added scientific gear weight, we decided to cut down on tents and bring only a single VE-25 tent for the four of us to sleep in. Needless to say, the tent was plenty warm due to the crammed bodies packed inside the tent at high camp!

Four of us squeezed in our VE-25 Tent at High camp! We were definitely warm enough! (photo: Blaine Horner)

We had a few more days of poor weather at high camp while waiting for a summit bid. In fact, we were not optimistic after two days of poor weather reports, unfortunately. However, one thing about mountains is that the weather reports change almost as often as the weather. After three days of waiting at high camp (with only one book to read between the four of us… Blaine wouldn’t read to us from it either!), we finally had a good weather report (or at least reasonable report) for the morning.

Looking up at the Autobahn which traverses up to the low point in the skyline, left of center. Wind and clouds at the summit on this day; We waited another day to climb to the summit. It was less windy (but still windy), snowing and more clouds unfortunately!

On June 23, we woke to relatively calm conditions at high camp, but cloudy conditions up high. Hoping it would clear up and deciding this was our weather chance to make the summit, we headed up the hill, first tackling the Autobahn, a well-known and treacherous portion of the route on a steep and icy slope that gains almost 1,500 feet of elevation from high camp to Denali Pass. Patrick and Blaine started out in front of Kristin and I, two rope teams in teams of two. We all reached Denali Pass relatively quickly but here is where the day became more interesting. Upon our arrival at Denali Pass, we found another team who had attempted to summit the day before. It turns out they had an accident that evening prior and one of their team members suffered a potential head injury. Following some discussion, the decision was made for Blaine to help these two stranded climbers down to high camp while I led Kristin and Patrick upward for our summit attempt. Blaine passed along his extra science gear to Patrick (which is how Patrick ended up with two heavy pieces of equipment) and we slowly started working our way up the hill in the fresh snowfall, wind, and in and out of the passing clouds.

We also passed another large guided party at Denali pass making our team the first roped team of the day to push forward towards the summit. Three solo climbers (no ropes) bounced in front of us, which we were quite happy with because they helped blaze a trail forward in the fresh powder snow which is exhausting to break trail in at over 18,000 feet! Our climb to the summit was slow, steady, and honestly relatively uneventful (which is a good thing!). We consistently checked on each other for warmth, comfort, and pace. Our slow and steady pace found us on the summit ridge within a few hours of departing Denali Pass. Unfortunately, the weather never really cleared up on the summit ridge. For those of you who live in the northeast U.S.A., it was basically like a good cloudy day in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains in New Hampshire: windy, cold, snowy, but all were manageable with a slow pace and focus on our health and comfort through the entire day. We reached the summit about 10 minutes before any other guided parties or roped teams reached it. At the summit we didn’t waste much time checking out the scenery because we really couldn’t see any! Kristin likens the view to the inside of a snowball. We were all pretty exhausted from the equipment haul as well, so we just set to work on our goal: to measure ice thickness with radar. Kristin, Patrick, and I combined the radar equipment into my pack, linked all the cables and batteries together, AND VOILA!!! The radar turned on, the GPS synced with the radar, and we were in business. This is not to say that we expected the system NOT to work, it’s only that in all of our collective experiences working in the field, it’s usually never easy, works right the first time, or something goes wrong! We were pretty psyched to get the system up and running on the first try. Unfortunately, the one thing that DID go wrong during our time on the summit is the arrival of other summit teams as soon as we got the radar system up and running. This meant that we had a limited amount of time or access to the summit because others surrounded the summit upon their successive arrivals. We completed three radar transects while near the summit: one from below and up to the summit marker, a second from the summit marker down slope, and a third that started down slope of the summit and traversed up and over the summit down a short portion of the West Buttress route. After 20-30 minutes we finished our survey work, snapped some photos of us at the summit, and were ready to head down. We were all tired and ready to make it back to camp but had several hours of slow downhill traverses to reach our comfortable sleeping bags.

Myself, Kristin, and Patrick at the summit of Denali. Not much of a view today unfortunately!

Collecting radar data at the exact summit of Denali!

- Setting up the GPR at the summit of Denali!

We returned to high camp around 9:30 pm after summiting, about 13 hours from start to finish: not a HUGE day by mountain standards but long enough to look forward to a good night’s rest. We made several rounds of water on the MSR stove, had a ramen and mashed potato dinner, and were curled into bed by midnight. The following morning, we were packing by 9:30 am, ready to make a long 14-mile, (10,000 foot elevation change) push back to base camp. We had another beautiful but climber-packed traverse from high camp down to Camp 14, arriving there around 3 pm. This traverse section of the route is our collective favorite part of the West Buttress climb due to the steepness of the ridge and amazing scenery. At Camp 14 we decided to take a mini-break to let temperatures cool down. We dug up our cache of gear, and spent a few hours lounging around in the sun. At 7 pm we started down the hill hoping to make it to Camp 11 within 3 hours. It was beautiful to Windy Corner, but at the top of Squirrel Hill we were met by white out and snowy conditions which persisted the rest of the way to Camp 1. But, temperatures were comfortable and we were all feeling pretty good. Kristin and I left Camp 14 first with Patrick and Blaine following about an hour behind. They traveled on skis making their descent more speedy and efficient than ours (our skis were cached at Camp 11). With the time differential, we all arrived at Camp 11 within 10 minutes of each other.

At Camp 11, we dug up our last buried cache, ate some smoked salmon and other snacks, and Blaine linked up with a friend who was kind enough to melt us some more water to save us time. Blaine and Patrick again relaxed for a little longer while Kristin and I started slowly down the hill in the whiteout, traveling wand to wand with hopes of reaching camp 1 in another 3-4 hours. Travel conditions were fairly atrocious on this leg of the route, unfortunately. With a thin crust of ice over water-saturated snow caused by warm temperatures, whiteout and snowy conditions making for poor visibility, and our tired selves, Kristin and I decided skiing was not a safe option. Unfortunately, with the skis off, the poor snow conditions caused us to post-hole slowly down the hill (post-holing means sinking into the snow up to our thighs upon every step). Despite sinking into the snowpack, we decided the personal control and ability to keep our rope tight between us while traveling on this potentially crevasse ridden region of the route, was more important than traveling faster (as in on skis). The talented skiers on our team (Blaine and Patrick!) were able to negotiate the route on skis, but skiing skill DEFINITELY played a role in their rapid successful descent!

Resting at Camp 14 after the summit and decent from Camp 17

View during our rest at Camp 14!

After a strenuous descent to Camp 1 arriving around 3 am, Kristin and I decided to set up camp for a few hours to get some rest. We had been on the go since 10 am the prior morning with a few stops at each camp. A little rest prior to completing the last 5.5-mile ski to basecamp would do us well! During the rest stop, I brewed some more hot water, enough for a couple glasses of hot apple cider, and then we rested for a few hours. I laid awake, listening to teams slowly trudge by us over the next couple hours. It’s a common occurrence for teams to “death march” from the summit back to base camp over 24-48 hours- a continuous push without setting up a camp and sleeping. Most of the teams that summited with us on June 23 were trying to do just that, each resting at various locations along the descent. After three hours, Kristin and I were ready to go again. After 30 minutes, we were packed up and had our skis on for the final trek back to basecamp. We arrived into basecamp after a relatively uneventful ski, around 10:20 am, over 24 hours since we departed high camp the day before and less than 40 hours from our successful summit of Denali. After a relaxing hour wait at basecamp we were on a flight back to town with Talkeetna Air Taxi.

Upon arriving in town, a shower, full pizza and calzone, ice cream, and relaxing on the town green was all in order. Great end to a successful field season. In a few months time (once we process data), we will distribute results of our field effort so folks can learn more about the science we accomplished this year. Overall, a fantastic team, a fantastic effort, great support from TAT, the park service, Compass Data, USGS, and a very enjoyable field season! Enjoy the many photos!

Drying equipment and gear out back at Talkeetna Air Taxi in Talkeetna…. my pants no longer stay up after loosing about 14 pounds over this last 2 months on Denali and by Mount Logan!